RSC 2009

For older versions, click here and here.

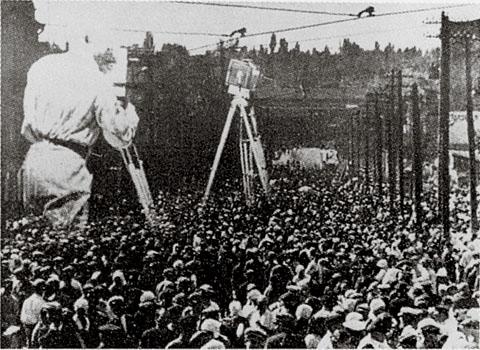

For excellence of acting and adherence to the spirit and intent of the play, this scores very high. Unfazed by issues of period and costume, it is rich in delightful anachronisms (like TV surveillance in the court) , thereby managing to focus on the psychological and spiritual issues which are the core of the great drama. In the fluidity of acting, whether it is in the leading roles of Hamlet, Claudius, Gertrude or Ophelia; the delightful Polonius or the comically modern gravediggers, it would be hard to match this TV film. Its hard to beat Brits when it comes to the Bard.

Hamlet as the play opens is reeling under the double blow of his father's demise and his mother's remarriage. The idyllic life of the gifted and intellectual Prince (easy to identify with his creator), dallying in the garden of a youthful romance, awaking to the wonder of life, is blown to smithereens . He sinks into melancholia, life having lost all fragrance and meaning.

But this is only the backdrop. The oracular appearance of the ghost, revealing the true nature of events, places on his inexperienced shoulders a sacred responsibility of revenge. No longer can he afford wallow in passive dejection. The task is far more than he is cut out to perform, and he embarks on the journey of his spiritual evolution. He toys with the idea of suicide, the famous soliloquy being perhaps the greatest meditation on death from a strictly rational viewpoint. He seeks an escape by questioning the veracity of the supernatural revelation. The intellectual escape route can be considered sealed by Claudius' reaction to the play within the play. This can be regarded as a scientific experiment or a piece of detective work. Now in question is only his own capability to rise to his responsibility, and the process of his inner congealing begins. In the inadvertent slaying of Polonius, he reaches a bridge of no return, since he has already carried out his duty in intent. But he is pursuing justice, not revenge, as his reservations in executing Claudius in the act of prayer import. From here onward is his evolution to the point where he grows to be equal to his task. The encounter with Fortinbras is a symbolic milestone. The parallel drama of Laertes' spurs him on.

The point of consummation of his resolve is the graveyard scene: his encounter with the death oif "beautious Ophelia" and Yorick's skull. He awakens to the nature of death and life: an "enlightened" man. This is the psychological climax of the play. He is "ready". The powers that be now take over, and events swiftly roll forward to the perfect symmetry of the denouement.

If one is to draw a meaning from the play, it would perhaps be that human beings are capable of change, all the more in the face of monumental challenges.

For older versions, click here and here.

For excellence of acting and adherence to the spirit and intent of the play, this scores very high. Unfazed by issues of period and costume, it is rich in delightful anachronisms (like TV surveillance in the court) , thereby managing to focus on the psychological and spiritual issues which are the core of the great drama. In the fluidity of acting, whether it is in the leading roles of Hamlet, Claudius, Gertrude or Ophelia; the delightful Polonius or the comically modern gravediggers, it would be hard to match this TV film. Its hard to beat Brits when it comes to the Bard.

Hamlet as the play opens is reeling under the double blow of his father's demise and his mother's remarriage. The idyllic life of the gifted and intellectual Prince (easy to identify with his creator), dallying in the garden of a youthful romance, awaking to the wonder of life, is blown to smithereens . He sinks into melancholia, life having lost all fragrance and meaning.

But this is only the backdrop. The oracular appearance of the ghost, revealing the true nature of events, places on his inexperienced shoulders a sacred responsibility of revenge. No longer can he afford wallow in passive dejection. The task is far more than he is cut out to perform, and he embarks on the journey of his spiritual evolution. He toys with the idea of suicide, the famous soliloquy being perhaps the greatest meditation on death from a strictly rational viewpoint. He seeks an escape by questioning the veracity of the supernatural revelation. The intellectual escape route can be considered sealed by Claudius' reaction to the play within the play. This can be regarded as a scientific experiment or a piece of detective work. Now in question is only his own capability to rise to his responsibility, and the process of his inner congealing begins. In the inadvertent slaying of Polonius, he reaches a bridge of no return, since he has already carried out his duty in intent. But he is pursuing justice, not revenge, as his reservations in executing Claudius in the act of prayer import. From here onward is his evolution to the point where he grows to be equal to his task. The encounter with Fortinbras is a symbolic milestone. The parallel drama of Laertes' spurs him on.

The point of consummation of his resolve is the graveyard scene: his encounter with the death oif "beautious Ophelia" and Yorick's skull. He awakens to the nature of death and life: an "enlightened" man. This is the psychological climax of the play. He is "ready". The powers that be now take over, and events swiftly roll forward to the perfect symmetry of the denouement.

If one is to draw a meaning from the play, it would perhaps be that human beings are capable of change, all the more in the face of monumental challenges.